Your Guide to Colic Surgery in the Horse

Updated March 29, 2024 | By: Andris J. Kaneps, DVM, PhD, DACVS, DACVSR

If your horse needed emergency colic surgery to save his life, would you have all the information needed to make a decision quickly? We’ll take you through the process from beginning to end to help you understand your responsibilities and tips for making the best decisions for your horse.

What Causes Colic in Horses?

Estimates are that 5 to 10% of the United States horse population experiences colic each year, with the vast majority (90 to 95%) being mild cases that resolve with simple medical management on the farm. However, the remaining 5 to 10% of horses with colic require referral to an equine hospital for intensive care or surgery. Why do some horses get better with the standard pain-killers, sedatives, fluids, laxatives, and lubricants (i.e. medical treatment) and others don’t?

There are many causes of colic, which is the shorthand term describing abdominal pain. Among the most common causes of abdominal pain are impaction of the colon with fecal material, which can cause gas, distension of the intestine, and severe pain. Gas trapped in the intestine may also cause twists or displacements of the intestine causing further pain. The twist may also lead to obstruction of the intestinal blood supply, potentially leading to loss of the affected bowel. Other causes include inflammation of the stomach or intestines with ulceration, formation of intestinal stones (enteroliths) that obstruct the colon, and intestinal tumors.

Medical vs Surgical Colic

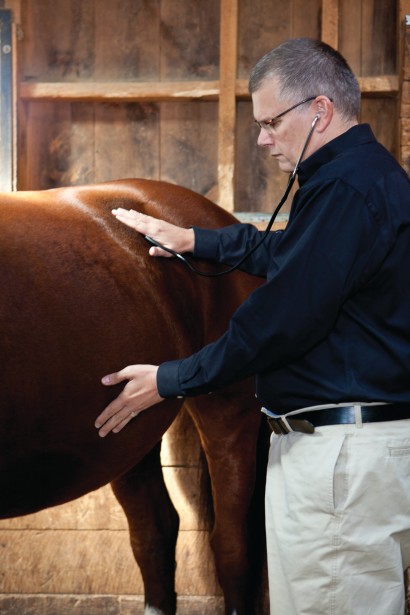

How does your veterinarian know when a colic is medical and can be treated conservatively on the farm, versus a colic that requires intensive care or surgical treatment at an equine hospital? At the initial examination, your veterinarian will ask questions regarding history, such as any past colics or changes in feed or activity. They will then perform an examination and provide initial treatment.

Your horse’s examination findings will help your veterinarian identify the severity of pain, presence of toxemia, and the presence or absence of intestinal motility. As well as an estimate of the hydration level and condition of the abdominal contents via rectal palpation and diagnostic ultrasound. In certain circumstances, samples of blood and abdominal fluid will be obtained and analyzed to further evaluate the severity of the colic. The horse’s response to initial treatments and the physical examination findings helps determine if intensive care or surgery at a hospital is needed.

Deciding Whether or Not to go to the Equine Hospital

Your veterinarian may suggest immediate referral to an equine hospital for further workup, additional medical support, or emergency abdominal surgery if:

- Heart rate consistently greater than 50 beats per minute.

- Absence of digestive sounds.

- Capillary refill time over 4 seconds or clinical signs of circulatory shock.

- Rectal palpation findings that include impaction, gas distension or displacement of intestines.

- The return of significant abdominal pain, such as the horse collapsing on the ground and rolling soon after pain relieving drugs have been administered may indicate a complicated colic that requires hospital care.

- There is a lack of response to medical treatment in general.

Colic Surgery Survival Rates and Post-Op Performance

Over the last 20 years or so, great strides have been made in colic surgery technique and general anesthesia safety, resulting in a much higher percentage of horses surviving and thriving after the procedure than ever before.

According to data from Practical Guide to Equine Colic edited by Louise Southwood (2013), survival rates for colic surgery range from 80 to 95%. Survival percentages vary with the type of lesion – where it is, what it is, and how it was resolved. For example, horses that require a resection of small intestine have, on average, a lower survival rate than horses that have a colon impaction that is easily cleared.

While many horse owners believe that older horses should not or cannot undergo colic surgery, those without other health issues have similar survival rates to younger horses. Dr. David Freeman reported in the 2012 American Association of Equine Practitioners (AAEP) Proceedings that horses older than 16 years – even those in their late 20s to early 30s –handled anesthesia and colic surgery well, with survival rates comparable to those of younger horses.

Riding After Colic Surgery

Most horses may return to light riding as soon as 2 to 3 months after surgery and a majority of horses return to their previous athletic activity. As reported by Davis and colleagues in the 2013 Equine Veterinary Journal, 76% of horses returned to their previous level of athletic activity within one year of colic surgery. In another study, 69% of thoroughbred racehorses returned to racing within 6 months of colic surgery (Tomlinson and collaborators in the Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 2013).

Costs of Colic Surgery

The type of colic, the severity of the condition, where in the country you’re located, and other factors all weigh into the final cost of colic surgery. Claims filed through SmartPak’s ColiCare™ Program during 2021 indicate that total costs of colic surgery nationwide, including pre-op and post-op care, can reach as high as $20,000.

Colic Surgery Insurance Coverage

Whether your horse is enrolled in a colic surgery reimbursement program like ColiCare or has insurance coverage that extends to colic surgery, owners and anyone with care, custody, and control of a horse must be familiar with the terms and conditions of these programs and policies. Things to ask yourself before being faced with a life-threatening decision to make include:

- Do I have to get prior approval from the company before agreeing to colic surgery?

- Does the company pay the vet or hospital directly or do I pay the bill and get reimbursed?

- Is there a deductible or co-pay and if so, how much is it?

- What things might void the agreement such as not disclosing previous colics?

- How do I submit a claim?

- When do I submit a claim? (that is, must I turn in paperwork and bills by a certain date?)

- What is the maximum payout and is there a limit per event or per year?

Not being able to say “yes” when the vet asks if surgery is an option is a terrible feeling, especially when your horse is enrolled in a reimbursement program or has an insurance policy. Save time and anxiety later by reading the fine print now and complying with all requirements.

What Happens at the Horse Hospital

If your horse requires attention at a surgical facility, expect an efficient team evaluation of your horse. Some of the same procedures done on the farm will be repeated, such as nasogastric intubation and rectal palpation. Your horse will likely have an intravenous catheter placed to allow the administration of fluids and medications. Additional laboratory tests will likely be undertaken. With the information obtained at the hospital, the clinician will determine the most appropriate means of treatment.

The Colic Surgery Procedure

The surgery is usually conducted under general anesthesia. The procedure involves an incision on the lower (ventral) surface of the abdomen, usually made along the line between the navel and sheath/udder. The abdomen is explored to determine the condition and location of the intestines and other abdominal contents. Abnormalities are resolved as necessary. For example: evacuating a fecal impaction, decompression of gas, untwisting bowel and returning it to its proper location, resecting a section of damaged intestine. When the abdominal abnormalities are resolved by the surgeon, the body wall is closed and the horse is recovered from anesthesia. The entire process of surgery through anesthesia recovery time may require 2 to 4 hours.

Potential Complications of Surgery

As reported by Proudman and colleagues (Equine Veterinary Journal 2002), the occurrence of at least one repeat colic occurs in 30 to 35% of horses that have undergone colic surgery. Of these horses, only 5% had more than 3 episodes of colic in 100 days after surgery.

Other complications include:

- lack of normal intestinal movement (ileus)

- abdominal incision infection or hernia

- infection or inflammation of the abdominal cavity (peritonitis)

- adhesions within the abdomen

- laminitis

- diarrhea

- pneumonia

Some complications occur immediately while the horse is still recovering in the hospital (typically between 5 to 10 days), and some occur when your horse returns to the stable (most often within the first 2 or 3 months following surgery).

Recovery and Care Post Colic Surgery

Discharge instructions usually address general monitoring, caring for the incision, feeding, exercise, and medication, if any. General monitoring includes observing your horse for normal appetite, water consumption, urination and defecation. Your horse should have normal rectal temperature, heart rate, respiratory rate, intestinal motility and alert, interactive behavior. The incision should be inspected daily for signs of infection such as discharge, excess swelling, or hernia formation.

Rehabilitation and Turnout

During stall confinement, neck and trunk stretches will help keep your horse flexible and interactive. Typically, recovery exercise begins with 4 weeks of stall rest with hand walking and grazing. The second 4-week period may include small paddock turnout if there are no incisional complications. At the end of this 8-week period, most horses may return to full turnout. Light lunging and riding is usually permitted during this time, with a gradual return to full training at 12-weeks following surgery.

Is Colic Surgery Worth it?

By answering some of the most common questions surrounding colic surgery – when a horse needs surgery versus medical care, which factors go into making the decision for an individual horse, and what to expect during and after – hopefully some of the “mystery” will be taken out of this procedure leading to improved outcomes for both horses and horse owners.