Colitis in Horses

By: Dr. Lydia Gray | Updated March 11, 2025 by SmartPak Equine

Simply put, “colitis” means inflammation of the colon, the segment of the horse’s large intestine after the cecum. The colon can become inflamed for a variety of reasons, from bacterial infections or a sudden diet change to antibiotic administration or stress.

Because equine colitis can range from a short, mild episode to a severe, life-threatening disease, it is important to recognize the signs early and get veterinary treatment started right away.

What is Colitis in Horses?

The word “colitis” describes a part of the body (“col” for colon) and how it is affected (“itis” for inflammation). It does not refer to a particular disease, the type of colitis, or its cause. Frequent, loose stools or diarrhea is one of the most common signs of colitis, although there may be other signs such as colic, fever, or weight loss depending on the cause.

Types and Causes of Colitis in Horses

Colitis in adult horses can be divided into two main types: infectious and non-infectious.

Infectious causes include:

- Bacterial infections such as from Salmonella, Clostridium, or Potomac Horse Fever

- Viral infections, such as Equine Coronavirus

- Parasitic infections (generally due to small strongyles)

Non-infectious causes include:

- Antibiotics

- NSAIDs (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs)

- Sudden feed changes

- Stress related to trailering, competition, exercise or management changes, illness, etc.

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease or IBD

- Sand ingestion

- Gastrointestinal lymphoma, a type of cancer of white blood cells

Right Dorsal Colitis in Horses

Right dorsal colitis (RDC) occurs in a specific segment of the colon, called the right dorsal colon. Also known as colonic ulcers, RDC has been linked to particularly high doses of NSAIDs or a reaction to an appropriate dose.

Involving ulcers of the colon lining and not just inflammation, signs in include diarrhea, recurring colic, weight loss, a reluctance to eat, lack of energy, fever, and edema.

Because the treatment and management of RDC is slightly different than that of a more general colitis, it is important to first have a veterinary diagnosis.

Signs and Symptoms of Colitis

When the colon becomes inflamed or irritated, often the first obvious sign is frequent loose stools or diarrhea. This is because when the natural microflora is disrupted and harmful bacteria multiply, the mucosa (inner lining) of the colon becomes damaged and is shed or sloughed off.

This affects the colon’s ability to carry out its normal functions of digestion and absorption. Fluids, electrolytes, and protein leak into the intestine and are passed out of the body into the stool.

At the same time, infectious or toxic substances can enter into the body from these leaks in the intestinal wall, leading to additional complications besides dehydration.

A horse with manure that becomes more “cow plop” in its consistency after a change in diet but who seems otherwise bright and healthy with a good appetite may not need to be seen by a veterinarian right away. However, a phone call to the vet explaining the situation is always a good idea.

Diarrhea that lasts longer than 24 hours, is profuse and watery, even explosive or “pipestream,” or that is accompanied by other signs such as colic, dullness, little to no appetite, fever, or purple or red gums instead of the normal pink should be examined by a veterinarian immediately.

Diagnosing Colitis

Ideally, the veterinarian will not only be able to make a diagnosis of colitis, but they will also be able to determine the cause so specific treatment can be given, such as antibiotics. However, the primary cause of colitis is never fully discovered in about half of all cases, meaning therapy is mainly supportive in nature and not specific.

The diagnosis of equine colitis begins with taking a thorough history, including the horse’s age, vaccination and deworming status. Your veterinarian needs to know whether any medications have recently been administered, as well as the diet and exercise program among other details.

Owners should be prepared to give a complete accounting of the current problem, such as:

- when the loose stool first started and what it looks like

- what other signs have been observed

- list of any treatments that were given and the result

- whether any other horses in the herd or barn are sick, and similar information

As part of the hands-on physical examination, the vet will assess all vital signs:

- temperature

- pulse or heart rate

- respiratory rate

- color and moisture of the gums

- capillary refill rate

- jugular vein refill rate

- gut sounds

- digital (fetlock) pulses

Blood, fecal, and abdominal fluid samples may be taken to test for the presence of infectious agents and to monitor the horse’s red and white blood cells as well as protein and electrolyte levels. In some cases, an ultrasound of the abdomen may be performed.

Treatment for Colitis

Some mild to moderate cases of colitis may be able to be treated on the farm, while other, more severe cases will need to be referred to a hospital for more intensive, round-the-clock therapy. The goals of therapy are to:

- Treat the underlying cause if known (infection, parasites, medication, etc.). In some cases, this may mean simply controlling the diarrhea through the use of intestinal protectants such as bismuth, kaolin, pectin, charcoal, smectite clay, or the yeast Saccharomyces boulardii. Some of these agents also have the ability to prevent bacteria from “sticking” to and damaging colon cells or to bind toxins, in particular the endotoxins released by bacteria that can leak into the bloodstream (endotoxemia).

- Replace lost fluids, electrolytes, and protein. If the physical exam or bloodwork shows the horse is dehydrated or has lost significant amounts of electrolytes and protein, it may be necessary to insert an intravenous (IV) catheter into the jugular vein of the neck and provide IV fluids. Depending on how sick the horse is as well as the degree of fluid and electrolyte loss, this may be a one-time treatment, may be spread over 24 hours, or may need to be given continuously for several days, requiring hospitalization and repeated monitoring of vital signs and bloodwork.

- Address pain, inflammation, and endotoxemia. Some horses with colitis also experience abdominal pain, or colic, which should be controlled both for their comfort and to reduce additional stress. It is also important to manage the inflammation associated with colitis and to prevent endotoxemia, which can lead to further complications. Because some of the medications used to address pain, inflammation, and endotoxemia are the same ones known to cause colitis in the first place, great care must be taken in selecting appropriate drugs and dosages

- Repair intestinal tissue and restore microflora balance. As the horse is kept hydrated and attempts are made to prevent the colitis from getting worse, it is also important to begin restoring the colon to normal health and function. This includes providing the building blocks of the cells that line the colon as well as the live, beneficial microorganisms (probiotics) and their preferred food source (prebiotics). The amino acid glutamine is recognized for its role in the renewal of healthy intestinal lining, including restoring immune function to the GI tract. Certain species and strains of bacteria, yeast, and protozoa are helpful when re-establishing the normal gut microflora as are soluble fibers such as psyllium, MOS, FOS, inulin, and others.

Part of treating colitis is ensuring that the nutritional needs of the recovering horse are met. Based on the severity of the case and the horse’s progress, this can range from only a slight adjustment in the normal diet to a gradual transition to a complete feed all the way to enteral (IV) nutrition.

Potential Complications

Colitis itself can be a serious condition, but it can also lead to secondary complications that can be just as serious, if not more so, than the GI disturbance that came first. These complications include:

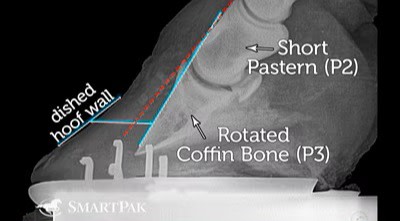

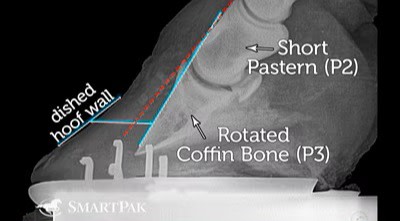

- Laminitis (inflammation of the lamina inside the hooves)

In severe cases, laminitis can lead to separation of the lamina from the hoof wall, visible in this x-ray as a rotated coffin bone. - Thrombosis (a blood clot) and other coagulation issues

- Circulatory shock because of low blood volume and the presence of endotoxins in the blood

- Secondary infections, such as pneumonia and at the site of IV catheter placement

Part of veterinary monitoring colitis cases involves observing for early signs of any of these complications and sometimes even taking measures (such as icing the feet or administering medications) to prevent their development.

Is Colitis Contagious?

There are several reasons why a horse with signs of colitis should be treated as if it has a disease which can spread to other horses.

- Even though colitis can be the result of a non-infectious and therefore non-contagious cause, in many cases the primary cause of the condition is never identified and so the mantra “better safe than sorry” is wise advice.

- It may take several days to a week or longer to get the results back from testing. If the sick horse has not been isolated and proper biosecurity measures put in place for handlers and other farm personnel during this time, it may be too late once the tests come back to prevent an outbreak.

- Even if the initial cause of the colitis was not a contagious disease such as Salmonella or Clostridium, these harmful bacteria may be present within the body of horses and illness, damage to the intestine, and a weakened immune system may allow them to multiply.

Recovery Time

The time needed for a horse to fully recover from a bout of colitis will depend on:

- the initial cause,

- how severe it was, and

- whether any complications occurred.

A horse that merely had soft stool for a day or two following a cross-country move may bounce back quickly because it did not lose any weight, become dehydrated, or lose significant amounts of protein or electrolytes.

However, a horse with Salmonellosis who required a lengthy hospital stay in the isolation ward with large volumes of IV fluid because of profuse, watery diarrhea for a week, a high fever, no appetite, and serious abnormalities in its bloodwork may takes several weeks to a month or longer to recover.

Fortunately, colon cells are regenerated every few days, so even if a large segment of bowel needs replaced, this can happen in a relatively short time.

Preventing Colitis in Horses

Some of the causes of colitis are more preventable than others. For infectious causes such as bacteria and viruses, experts urge horse owners to practice good biosecurity when co-mingling horses, such as at shows and other events. Work with a veterinarian to develop an effective parasite control program to prevent inflammation in the colon due to small strongyles.

For the non-infectious causes, the advice differs between the various causes:

- Antibiotics: Only give antibiotics to horses under the direction of a veterinarian.

- NSAIDs (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs): Try to limit the use (dosage and frequency) of non-steroidal drugs such as Flunixin Meglumine and Phenylbutazone (Banamine® and bute, respectively), and others, especially in horses with a history of RDC.

- Sudden feed changes: make adjustments to the diet, both hay and grain, gradually, over at least 7 to 10 days.

- Stress related to trailering, competition, exercise or management changes, illness, etc.: As much as possible, try to keep the same schedule and diet with horses while travelling, and allow time for rest and recover after transport and events.

- Sand ingestion: Avoid feeding horses where they could pick up sand with their food, and consider a monthly purge with a psyllium-based product.

Horses with a normal, healthy hindgut that includes a balanced microbial population may be less likely to experience episodes of colitis. Following the “best practices” of feeding, turnout, exercise, and other care could protect horses from inflammation and irritation of the colon.