Gastric Ulcers in Horses

Updated March 29, 2024 | By: Andris J. Kaneps, DVM, PhD, DACVS, DACVSR

Research has shown that over 90% of racehorses and 60% of performance horses – hunter, jumpers, dressage, endurance, and western – have ulcers (Equine Gastric Ulcer Syndrome [EGUS]). Studies have also shown that even small changes in the routine of recreational horses can cause gastric ulcers in as little as five days, meaning your horse does not have to undergo serious stress or be in intense training to develop ulcers [1].

How Gastric Ulcers Form

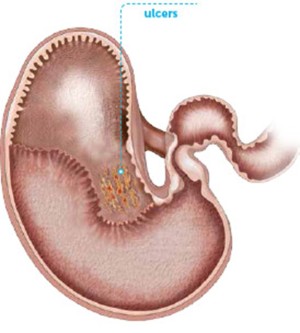

The word “gastric” means “of or pertaining to the stomach,” so, gastric health focuses entirely on one organ —the stomach. Your horse’s stomach is covered with two types of linings:

- Glandular mucosa - contains glands that constantly produce acid to aid in digestion and covers the bottom 2/3 of the stomach. This region produces mucus and bicarbonate to help protect the stomach from acid exposure. The medical term for ulceration of the glandular mucosa is Equine Glandular Gastric Disease (EGGD).

- Non-glandular (squamous) mucosa - covers the top 1/3 of the stomach. This area is where stomach contents are mixed, usually with buffering from food and saliva so it doesn’t have as much natural protection from acid as the glandular mucosa. The tissue edge that separates the squamous from glandular mucosa is called the margo plicatus. The medical term for ulceration of the squamous mucosa is Equine Squamous Gastric Disease (ESGD).

The longer your horse’s stomach is empty, the more at risk he is for developing squamous gastric ulcers because the acid in his stomach isn’t being buffered by forage and saliva [2]. Excess acid can damage the unprotected squamous mucosa and erode through the tissue, creating painful ulcers.

Signs of Ulcers in Horses

Signs of gastric ulcers can be subtle and may include:

- Decreased performance (often mistaken for musculoskeletal or back pain)

- Poor body condition

- Weight loss

- Dull hair or coat

- Reduced appetite

- Behavioral issues or a poor attitude (girthiness, irritability, resistance, etc.)

- Repeated colic

Risk factors or causes of gastric ulcers

- Stress (caused by training, competition, shipping, injury, changes in herd, etc.)

- Infrequent feeding or long intervals between feedings

- High grain intake (high starch levels, low fiber levels)

- Limited access to hay/pasture

- Frequent intense training and competition

- Reduced access to water

- Lack of free-choice contact with other horses

- Shipping

- What is playing on the barn radio (music reduces occurrence of ulcers, talk radio does not!)

[2,4,5]

These risk factors may also lead to weight loss and other signs in your horse that are not due to ulcers. Also, prolonged training and competing at gaits faster than the walk may result in contraction of the stomach and splashing of gastric acid on the squamous mucosa, potentially resulting in formation of ulcers [3].

Many of the same causes of squamous ulcers likely cause glandular ulcers, but they aren’t clearly identified [2]. The presence of bacteria (Helicobacter pylori) is associated with human gastric ulcer disease, but bacteria have not been found to cause equine gastric ulcers.

Ulcers and Colic

The word colic simply means “abdominal pain,” so pain from ulcers would fall under the larger umbrella of pain in the abdomen, or colic. So, a horse suffering from painful ulcers in the stomach is already experiencing colic. Typically, abdominal pain due to gastric ulcers is described as mild, intermittent, and recurring colic [2]. There are other conditions that may cause mild, intermittent, or recurring colic, which is why a veterinary diagnosis is so important.

Do horses with ulcers have higher instances of colic episodes?

It’s hard to know which comes first: inflammation in the intestinal tract causing pain and stress so the horse subsequently develops gastric ulcers, or the presence of ulcers in the stomach causing the rest of the gastrointestinal tract to be dysfunctional, resulting in colic pain of small intestine, cecum, or colon origin.

Since gastric ulcers and colic originating in the intestines share many of the same risk factors, a horse who is prone to stomach lesions might also be prone to problems in other parts of the digestive tract.

Diagnosis of Gastric Ulcers

The only way to determine if a horse has stomach ulcers is to perform a gastroscopy. This examination requires the passing of a flexible viewing scope into to the horse’s stomach to evaluate the mucosal surfaces of the stomach. It entails preparing the horse for gastroscopy by withholding feed (for 12-16 hours) and water (for 2-4 hours), and typically administering mild sedation.

Ask the Vet Video on Diagnosis and Treatment for Ulcers in Horses

Endoscopic Images of Ulcers in Horses

Prevention and Treatment of Ulcers in Horses

- Turn your horse out as much as you can. Ideally, horses should be kept on pasture 24/7.

- Feed frequent, small hay meals. The constant intake of forage and production of saliva naturally buffer the stomach against gastric acid. If fresh grass is not available or appropriate for the horse, provide free-choice grass hay.

- Try using a small-hole hay net filled with grass hay to recreate the healthy grazing experience of “trickle feeding” all day long.

- Adding small rations of alfalfa to your horses forage intake can help to reduce acidity in the stomach as alfalfa is naturally higher in protein and calcium, which act as natural pH buffers. Alfalfa should only be fed in limited amounts, rather than free choice.

- Feed the minimum a mount of grain necessary to meet the horse’s energy requirements, and always spread the total amount of grain over multiple, small meals. Large grain meals can increase acid levels in the stomach, increasing your horse’s risk for gastric ulcers.

- Find ways to reduce stress in your horse’s life. When you take your horse somewhere, try to keep his schedule and environment as close to what it is at home as possible. Make sure you give your horse some "down time" if his training and competition schedule is especially grueling.

- Limit the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDS) such as bute (phenylbutazone) and Banamine® (flunixin meglumine). These medications inhibit enzymes that protect the squamous and glandular mucosa and with dosing above recommendations or prolonged use may lead to gastric ulcer formation.

Supplements that May Support Stomach Health

Supplements designed to support gastric health often include a combination of these key ingredients:

- Antacids to buffer or neutralize and soothe the stomach (like calcium or magnesiumcarbonate)

- Licorice to help restore healthy stomach tissue

- L-Glutamine to help promote healing

- Soluble fiber to help form a protective layer over erosions

- Plant adaptogens – such as sea buckthorn, Aloe Vera, pectin, and lecithin – may help horses better manage ulcer-causing stress

Research has shown that certain gastric supplements can be effective is supporting stomach health for horses that are under stress. A study led by Louisiana State University School of Veterinary Medicine found that adding SmartGut Ultra to feed prevented non-glandular gastric ulcers from worsening.

Horse Ulcer Medications

All recommendations for treatment of your horse’s ulcers must be made by your veterinary team considering your horse’s general health and medical condition. Treatment for squamous ulcers is usually required for 30-60 days, while treatment for glandular ulcers often requires 60-90 days. Some horses require long-term therapy, and many horses benefit from preventive treatment when they are transported, starting training, or going on the show circuit.

GastroGard® and UlcerGard

The first and only FDA-approved prescription medication for treating ulcers is GastroGard®. It contains the active ingredient omeprazole which works by shutting down the production of gastric acid, allowing the ulcer(s) to heal. UlcerGard is the non-prescription version of GastroGard and is labelled for maintenance therapy to prevent ulcers.

Both GastroGard and UlcerGard have the same concentration of omeprazole in the same paste formulation. However, their directions for administering the medication differ. For horses in training, omeprazole has been shown to effectively reduce the occurrence of gastric ulcers [6].

Other Ulcer Medications

Cimetidine and ranitidine are two prescription medications used successfully to treat and prevent ulcers. Because they are not FDA-approved for use in horses, this is considered “extra-label” use.

Sucralfate is an oral medication which is often included in treatment or prevention of ulcers [7]. Sucralfate will adhere to ulcers and form a barrier that protects against acid, stimulate production of gastric mucus, and increase levels of healthy prostaglandins that promote healing.

Misoprostol is most commonly included for treatment of glandular ulcers [7,8]. It is an orally administered equivalent of healthy gastric prostaglandin that reduces gastric acid production, stimulates mucus production, and increases local blood flow.

Keep in mind, your vet is your best resource when it comes to the treatment of ulcers in your horse. Your horse is unique and may take a combination of therapies and changes in their day-to-day management to find what works best.

Evidence-Based References

- McClure SR, Carithers DS, Gross SJ, Murray MJ. Gastric ulcer development in horses in a simulated show or training environment. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2005 Sep 1;227(5):775-7.

- Sykes BW, Hewetson M, Hepburn RJ, et al. European College of Equine Internal Medicine Consensus Statement--Equine Gastric Ulcer Syndrome in Adult Horses. J Vet Intern Med. 2015 Sep-Oct;29(5):1288-99.

- Lorenzo-Figueras M, Merritt A. Effects of exercise on gastric volume and pH in the proximal portion of the stomach of horses. Am J Vet Res 2002;63:1481–1487.

- Sykes BW, Bowen M, Habershon-Butcher JL, Green M, Hallowell GD. Management factors and clinical implications of glandular and squamous gastric disease in horses. J Vet Intern Med. 2019 Jan;33(1):233-240.

- Pedersen SK, Cribb AE, Windeyer MC, Read EK, French D, Banse HE. Risk factors for equine glandular and squamous gastric disease in show jumping Warmbloods. Equine Vet J. 2018 Nov;50(6):747-751.

- Mason LV, Moroney JR, Mason RJ. Prophylactic therapy with omeprazole for prevention of equine gastric ulcer syndrome (EGUS) in horses in active training: A meta-analysis. Equine Vet J. 2019 Jan;51(1):11-19.

- Pratt, S. L., Bowen, M., Hallowell, G. H.,Shipman, E., Bailey, J., & Redpath, A. (2023). Does lesion type or severity predict outcome of therapy for horses with equine glandular gastric disease? – A retrospective study. Veterinary Medicine and Science, 9, 150–157.

- Varley G, Bowen IM, Habershon-Butcher JL, Nicholls V, Hallowell GD. Misoprostol is superior to combined omeprazole-sucralfate for the treatment of equine gastric glandular disease. Equine Vet J. 2019 Sep;51(5):575-580. Epub 2019 Mar 21. Erratum in: Equine Vet J. 2020 Nov;52(6):894.