Equine Metabolic Syndrome

Updated June 14, 2022

- What Breeds are Most Affected and Why

- How Equine Metabolic Syndrome Is Diagnosed

- EMS vs Cushing's Disease

- Treatment and Management of Equine Metabolic Syndrome

- Supplements to Support Normal Metabolic Function

Equine Metabolic Syndrome (EMS) links the risk factors of accumulation of fat and the inability of insulin to do its job to the development of laminitis in young to middle-aged horses and ponies. It occurs when there is a “perfect storm” between a horse’s genetics and the environment, as when “easy keepers” are given access to too many calories (especially from simple carbohydrates) and not enough exercise.

Researchers are learning more and more about EMS such as what breeds are most affected; how to best identify horses with it; how it’s related to the endocrine disease PPID (Pituitary Pars Intermedia Dysfunction or Cushing’s Disease); and what can be done in terms of diet, exercise, and medication to manage it.

What Breeds are Most Affected and Why

EMS is most commonly seen in breeds thought of as “easy keepers,” horses and ponies able to put weight on and keep it on even when they don’t seem to eat very much. Breeds that evolved to survive in harsh environments where certain seasons are cold and wet and vegetation is sparse are said to have a “thrifty” gene. While this may have been an advantage to the horse fending for itself, it’s a disadvantage to the modern horse provided with limited turnout, high-calorie diets, and lush pastures. Breeds at a higher risk for EMS due to this particular genetic predisposition include:

- Pony breeds (of British descent) such as Welsh, Dartmoor, Shetland

- Morgans

- Andalusians

- Gaited breeds such as Saddlebreds and Paso Finos

- Miniature horses

- Warmbloods

While EMS is typically seen in some breeds over others, it can affect all breeds of horses if put into the wrong environment with inappropriate management. Mares and stallions/geldings are equally affected, with most horses between the ages of 5 and 15 when the first signs of EMS occur, such as laminitis.

How Equine Metabolic Syndrome Is Diagnosed

History, Signs, and Exam of Clinical Presentation

While it is true that many horses and ponies with EMS are obese, not all are. So, obesity alone cannot be used to confirm the condition. In fact, the Equine Endocrinology Group, experts who prepare written guidelines to help practicing veterinarians diagnose and manage EMS and PPID, puts horses with EMS into one of three categories:

- Obese EMS

- Lean EMS (normal body condition score overall with fat deposits or regional adiposity such as a cresty neck)

- Obese or Lean EMS with coexisting PPID

In addition to regional adiposity in the neck, other common locations of lumpy fat pads are behind the shoulder, around the tail head and rump, and in the sheath of geldings or udder of mares.

Laminitis, the breakdown of the laminar tissue in the feet which hold the hoof wall to the hoof bone, is also a common sign of EMS. It may have been so subtle as to have gone unnoticed in the past -- while leaving evidence such as rings in the hoof wall or rotation on X-rays -- or may be the current cause of severe pain while walking or standing.

Role of Insulin in Horses with EMS

Horses with these signs – obesity, fat pads, and laminitis – have one thing in common, and that is an abnormal insulin response to sugars and starches in the diet (non-structural carbohydrates or NSC). Insulin, a hormone produced by the pancreas in response to a meal, assists glucose (blood sugar) into cells for use or for storage.

The failure of the body’s metabolically active tissues to respond properly to insulin is known as insulin resistance or IR. While abnormally high levels of insulin in the blood is called hyperinsulinemia or HI. Together, these abnormal insulin responses to sugar are referred to as insulin dysregulation, considered the hallmark of EMS. Fortunately, today there are simple blood tests that can quickly measure a horse’s insulin response to sugar.

Blood Testing for EMS

Known as dynamic tests because the veterinarian stimulates the horse’s system and then measures its response over time, the preferred test is the Oral Sugar Test. After fasting, the vet administers corn syrup by mouth and then draws blood 60 and 90 minutes afterward to check insulin levels.

A shorter test that does not require fasting (but is also not as sensitive) is the Insulin Tolerance Test. Here, the vet draws blood first, administers insulin, then draws blood again 30 minutes later to check blood glucose levels. Single measurements of insulin and/or glucose concentrations have their place in the management of EMS but are not considered the “gold standard” for diagnosing the condition.

EMS vs Cushing's Disease

Cushing’s Disease, or PPID, is a collection of clinical signs due to the overproduction of certain pituitary hormones. In the early stages of the disease, these clinical signs include:

- any sort of hair coat change (however subtle) such as delayed or patchy shedding

- loss of muscle in the topline

- a decrease in athletic performance

- change in attitude (such as lethargy)

- change in sweating (either an increase or decrease)

Experts say that most of the time the development of laminitis is not necessarily a sign of PPID, but can be a comorbidity, or when more than one disease is present at the same time.

Horses with a history of EMS are at a higher risk for PPID, especially as they age. Therefore, it’s important to test horses with EMS for the presence of PPID since Cushing’s Disease has an FDA-approved treatment that may slow the progression of the disease. It’s also important to test horses with PPID for the presence of EMS (insulin dysregulation) since an abnormal response to insulin can make controlling Cushing’s Disease that much more challenging.

Treatment and Management of Equine Metabolic Syndrome

While certain prescription medications can play a role in the management of Equine Metabolic Syndrome, there is no FDA-approved drug to treat EMS like there is with PPID. Veterinarians recommend a combination of diet, exercise, and medical therapy to achieve a healthy weight, reduce insulin concentrations, and lower the risk of laminitis.

What to Feed a Horse with Equine Metabolic Syndrome?

Nutritional recommendations for EMS depend on whether the horse is obese or lean. Since all horses and ponies with Equine Metabolic Syndrome can have an abnormal insulin response to sugars and starches in the diet, it is important to keep the levels of these non-structural carbohydrates (NSC) below approximately 10%. This means:

- removing grains or concentrates from the diet and replacing it with either a low NSC ration balancer or a vitamin/mineral supplement so that the horse’s daily protein, vitamin, and mineral requirements are met

- restricting pasture or even completely eliminating grazing, especially when NSC levels are high such as in the spring and fall

- providing low-NSC hay, which means testing hay for NSC content. If slightly high, soak the hay for 30 minutes in warm water or 60 minutes in cold water before draining and feeding

Obese EMS horses may need to be kept off pasture completely, such as in a dry lot or paddock. Lean EMS horses may be allowed limited grass access through the use of a grazing muzzle and only when sugars and starches are lowest, from late afternoon to early morning hours.

While NSC must be limited for lean EMS horses, it’s important to ensure they’re provided with the necessary calories to maintain good body condition. Adding a fat supplement to their diet is one way to provide additional safe calories. Working with a qualified equine nutritionist who can fully assess what diet is best for your unique horse is the best strategy.

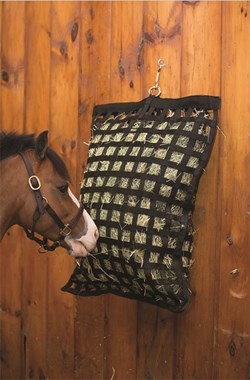

Providing low-NSC hay in either a slow-feeder or small-hole hay net slows the rate of intake, making the hay last longer while prolonging the time spent eating. This is especially helpful for the obese horse who may also have the daily amount of hay restricted to 1.5% of body weight until weight loss occurs.

Exercise for Horses with EMS

This disclaimer for workout videos and equipment in people could just as easily be applied to horses:

“To reduce the risk of injury, before beginning this or any exercise program, please consult a healthcare provider for appropriate exercise prescription and safety precautions.”

That is because exercise recommendations for EMS must take into account whether the horse or pony is currently in a bout of laminitis or is sound and pain-free. Also just like in people, research in horses suggests that exercise not only helps reduce weight, but it also helps improve insulin sensitivity in those affected with metabolic syndrome. In non-laminitic horses, all levels of exercise are beneficial in burning calories and improving insulin sensitivity. Horses should be introduced to exercise gradually at the direction of a veterinarian with the intensity and duration increased slowly over time.

Medical Therapy for EMS

When a horse or pony with EMS does not respond to changes in diet and exercise, the veterinarian may prescribe oral medication to jumpstart weight loss and improve insulin sensitivity. Most commonly used is a dose of Thyro-L (levothyroxine sodium) for 3 to 6 months while feed is restricted. Once the desired weight loss is achieved, the horse can be gradually weaned off the product. The second drug is metformin, used to treat Type II Diabetes in people. Unfortunately, it is poorly absorbed in horses and doesn’t appear as successful in improving insulin sensitivity.

Preventing Equine Metabolic Syndrome

EMS can lead to serious issues such as laminitis, and, while it cannot be cured, it can be prevented and managed. Veterinarians advise owners of high-risk breeds to observe them closely for early signs of EMS (such as fat deposits) and to routinely have dynamic blood tests performed to check for an abnormal response to insulin. Rather than waiting for a bout of laminitis to occur or for blood tests to come back positive, owners of horses at-risk for EMS can already be focusing on maintaining normal weight in their horses through appropriate diet and exercise.

More on Supplements that May Support Metabolic Function

- Equine metabolic supplements to support a normal metabolism

- Our metabolic supplement comparison chart

Special thanks to Dr. Amanda Adams of the University of Kentucky’s Gluck Equine Research Center, who focuses on equine immunology in aging, obesity/metabolic syndrome, and stress, for her thoughtful and thorough review of this article.

Article First Published June 2008SmartPak strongly encourages you to consult your veterinarian regarding specific questions about your horse's health. This information is not intended to diagnose or treat any disease, and is purely educational.